Ecocriticism, Grasslands, and Women’s Settler Colonial Narratives in the U.S. and Australia

Presented at Washburn University

Topeka Kansas, Nov. 12, 2018

Tom Lynch

On November 12, 2018, I gave an invited presentation to the Center for Kansas Studies at Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas on the topic of settler colonialism in the US and Australia. It was based on my research and articles on women’s frontier gardening. Here is the text of the talk, along with the powerpoint. Thanks to Vanessa Steinrotter and all the folks at the Center for Kansas Studies for the opportunity.

When I began this project, nearly 18 years ago, it was intended to be an ecocritical comparison of US-Australian desert literatures. But as I worked my way into it and procrastinated completion, I discovered in emerging Australian scholarship an orientation to literature, history, and culture, (especially but not exclusively to literature of frontier, settlement, and arid places), that was to transform the way I thought about both Australian and US literature: settler colonial theory. Through this lens, I grew to see American literature and culture, especially in the West, quite differently than I had before.

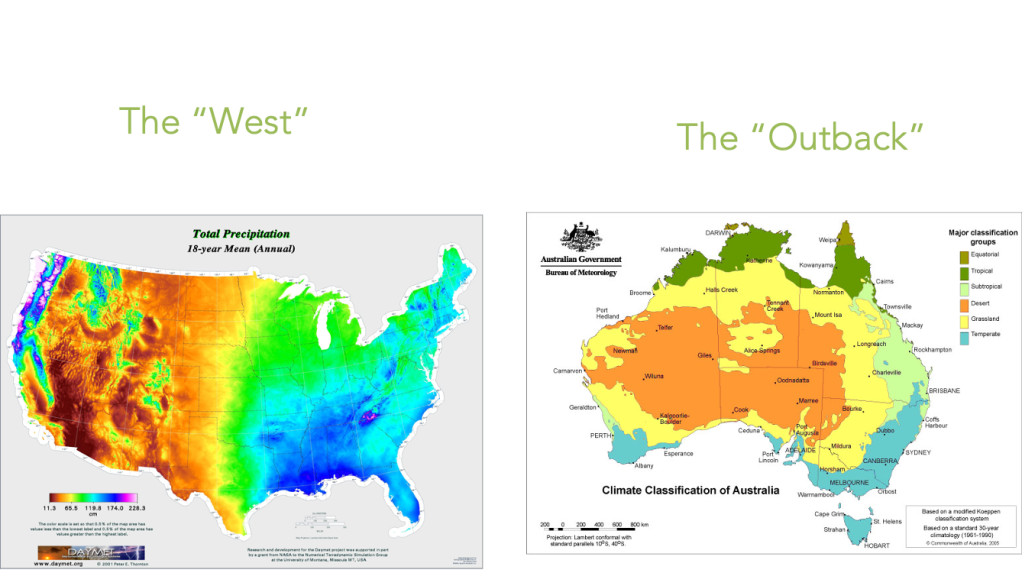

Let me first note that the terms “The West” and “The Outback” have considerable cultural cachet, are globally recognized, but they are in fact rather amorphous locations. For the purposes of my project, I define both the West and the Outback bioregionally. That is, they comprise the arid and semi-arid regions of their respective countries, the geographers “dry domain,” colored in yellows and browns and reds on these map. (It’s one reason we don’t think of “Westerns” as situated in the rainy and heavily forested Pacific Northwest, colored in blue.)

Most settler colonial studies efforts engage with the treatment and status of Indigenous people, or with how settler societies negotiate and claim their own distinct identity and sovereign status vis a vis Indigenous societies, on one hand, and the imperial metropole, on the other–appropriate and urgent areas of inquiry. But I have also found it to be an especially pertinent orientation for thinking about how literature both informs and reflects our relationship to the natural world, the domain of ecocriticism.

Patrick Wolfe, an early developer of settler colonial theory, offered that “elimination of the Native” is the central tenet of settler colonies. He was referring to Native people, but his claim is equally true for native flora and fauna, especially in arid and semi-arid regions, including, especially, grasslands.

In the United States, the history of the English-speaking settlement of the West is usually portrayed as a unique historical undertaking. While every place has its own distinctive history, it is equally true that this settlement was part of a much broader colonial phenomenon: the expansion of European, and in this case English-speaking, settler societies around the planet.

In addition to the US, this settlement occurred most notably in Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, and Australia. What I learned from my Australian studies was this key aspect of settler colonial theory, the need to situate the history, culture, and literature of the West within this broader context of a global pattern of Anglo-settler frontiers, especially those in comparable arid and semi-arid regions of the world.

The West and the Outback have some remarkable natural and cultural parallels that lend themselves to ready comparison.

They are both arid and semi-arid regions that have been colonized by primarily English-speaking settlers who have sought to impose cultural ideas and modes of living that evolved in, and are better suited for, much wetter climates.

Some of the specific parallel cultural experiences, all of which inform literary representations in varying degrees, include but are by no means limited to the following:

— the European exploration, claiming, and mapping of the new territories in a manner that included itemizing biological, geological, and other “natural resources.” (Lewis and Clark, Zebulon Pike, etc. have their Australian counterparts in Burke and Wills, Charles Sturt, etc.)

— the suppression and displacement of Indigenous peoples; sometimes this took the form of outright warfare or other violence, such as forcible child removal, but often it is reflected today, especially in the US, by a marginalization, if not a total erasure and collective forgetfulness of, prior Indigenous presence.

— the creation of a regional frontier mythology that was crucial to the formation of a national identity; this mythology persists in many ways, including in the proposition that people allied with rural frontier culture are more real or authentic representatives of national identity than are other citizens: REAL Australians live in the Outback, REAL Americans live in rural areas, especially in the West.

–a variety of homesteading schemes in which the government would give land that had been seized from Indigenous people away to settlers in exchange for their living on and “improving” the land. Australia’s first homestead act, the Robertson Lands Act in New South Wales, predates the US Homestead Act by one year. These improvements typically involved wholesale conversion of landscapes from indigenous flora and fauna to introduced flora and fauna along with the necessary infrastructure to support such a change. Entire rich biomes (such as the tallgrass prairie) fell to the plow, were intensively logged, or were similarly destroyed in a process that can only be considered ecocide.

— the emergence of frontier outlaw heroes who, whatever the realities, project a sort of Robin Hood like appeal. Such characters loom large in the cultural imaginaries as reflected in numerous novels and films, but their overall significance is rather slight.

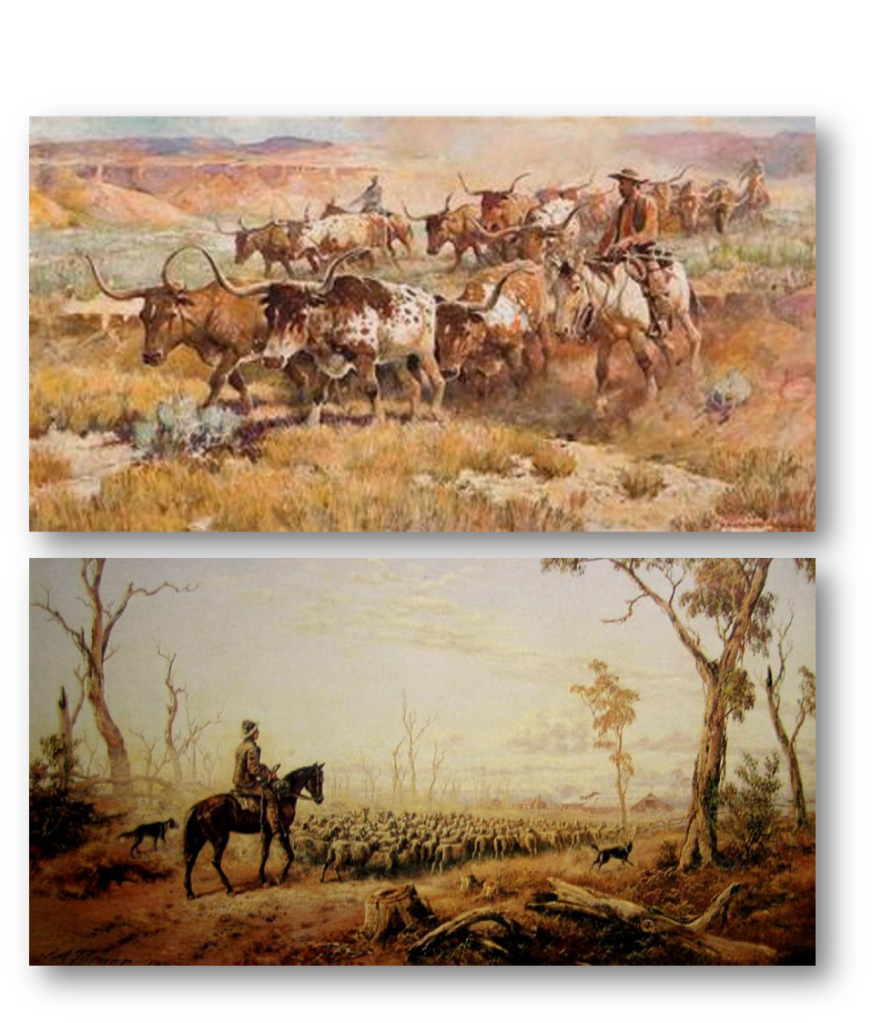

— the introduction of a pastoral economy involving sheep and/or cattle ranching. The cowboy in the West, and the shearer or drover in Australia, take on mythic dimensions in both places. In order to create a welcoming home for such pastoralism, many native animals were destroyed, either because they competed for forage or because they were predators, and imported and often invasive grasses were intentionally spread over wide areas.

— though often celebrated as very eco friendly and innocent (note the children), in many settler colonial contexts tree planting and other afforestation efforts such as Arbor Day cause serious environmental harm. (As I’ll discuss in more detail later) Such projects arose as a response to the perceived deficiencies of native steppes and grasslands, which settlers sought to replace with imported trees, contributing to the degradation of prairie and desert grassland ecologies..

— the creation of dust bowl conditions due to inappropriate agriculture or overgrazing, along with a host of other problems such as invasive species, water shortages, native species decline, and other ecological difficulties too numerous, alas, to itemize.

— the testing of nuclear weapons and the storage of nuclear (and other highly toxic) waste.

–the creation of various irrigation schemes, whether massive dam project or the depletion of aquifers via center pivot technology, in order to “reclaim” arid lands and to make them suitable for industrial scale agriculture.

— the construction of a growing tourism economy, including a system of National Parks, wildernesses, and other protected areas.

— a related growing ecological awareness that challenges historical settler land tenure practices and that seeks to restore some aspects of pre-colonial environmental conditions.

— and a revival of Indigenous communities both culturally and politically in a manner that works to reclaim lost lands and cultural heritage.

There are also, I should point out, some notable differences. For today, I will note just two.

–there is no frontier gunfighter tradition in the Outback, a feature so common in the popular imagination regarding the West as to be, for many people, definitive. The code of mateship in the Outback allowed for plenty of fisticuffs–one can fairly beat the crap out of ones mates–but gunplay was considered unsporting and cowardly. It’s notable that Australia had to import Quigley when they needed a gunfighter.

— Another particularly interesting and significant difference is that in Australia the Aboriginal populations were often not displaced from their traditional lands, but were instead coerced into employment on cattle and sheep stations as domestic help and as stockmen. This enabled them to maintain ties to their traditional countries, even if they had to sacrifice much of their agency. It has also offered interesting opportunities today for them to reclaim title to their land under the new policies introduced in the wake of the Mabo and Wik court decisions that have set in motion a series of Indigenous land claims.

To paraphrase Patrick Wolfe, settler colonialism is an enduring social, cultural, ideological, and political structure not a singular historical event that we have moved beyond. It did not end with the “closing of the frontier,” but continues to operate in the contemporary world. There is no “post” in settler colonialism.

In my project I refer to the basic ideological and imaginative framework sustaining and motivating the Anglophone settler experiences in the West and the Outback as the settler colonial imaginary.

Like any sociocultural project, this imaginary envisions the world and its relationship to it in a particular way and generates an all pervasive discourse and symbolic system to enforce that perspective. Though local accents may inflect its expression a bit differently, the settler colonial imaginary is remarkably similar in both the U.S. and Australia. And it is sanctioned, empowered, and maintained via a constellation of integrated and recurring values, images, icons, archetypes, monuments, stories, discourses, lexicons, politics, forgettings, and expectations which, if not always identical yet retain obvious resemblances.

One of these similar expressions of the settler colonial imaginary, and the one I want to focus on today, involves the replacement of native flora with imported plants in acts of gardening and other horticultural interventions.

As I have noted, a key element of settler colonial ideology is the “elimination of the native,” which can apply not only to people but also to native flora and fauna. In Australia, this notion often goes under the name of terra nullius, and asserts that prior to the arrival of Europeans the land belonged to no one, at least to no one whose rights a white person had any obligation to respect. In this regard, in the US context, there is no clearer expression of the settler colonial ideology of terra nullius than that uttered by Willa Cather’s Jim Burden at the beginning of My Antonia. When, as a boy, he is crossing the tallgrass prairies of southern Nebraska, he peers out of his wagon and remarks in this well known and oft honored statement:

There seemed to be nothing to see; no fences, no creeks or trees, no hills or fields. If there was a road, I could not make it out in the faint starlight. There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made. No, there was nothing but land . . . (7)

This passage encapsulates the settler colonial imaginary more succinctly and memorably than any other I have encountered.

The land is empty, a “nothing but” and awaits European settlers to transform it into a something. Cather, in particular, seeks to sidestep the implicit ethnic cleansing in this idea by placing her Nebraska stories in that period immediately following the forced expulsion of the Natives, whose ties to the land can thereby be conveniently ignored.

Of course removing the Indigenous people is but a first step to the conversion of a nothing into a something. Subsequent steps involve the elimination of much of the Indigenous flora and fauna and its replacement by species imported primarily from the home of the settler colonial people, creating a sort of neo-Europe.

One of the parallels between the US and Australia is the presence of both fiction and non-fiction narratives reflecting settler women’s experiences. Typically in these narratives women participate with men, though in different spheres, in the struggle to convert what they perceive to be wilderness into a domesticated space that seeks to replicate the natural environment of the place of origin. This frequently involves the replacement of native flora and fauna with imported varieties, most obviously in our bioregion the replacement of bison with imported livestock and the subsequent effort to eliminate animals, from wolves to prairie dogs, that were perceived to hinder that transformation.

While today the behavior of men on the frontiers of settler colonial society is often recognized to have been ethically suspect, the actions of settler women are normally seen to have been more benign. And indeed I want to focus on behavior that seems especially innocent, the planting of gardens, particularly flower gardens and ornamental shrubs and trees. For the purposes of this paper, I am going to ignore the planting of non-native plants for food, such as vegetables and fruit trees, which can be justified on different grounds, and consider only the plants used for aesthetic purposes, that is, flower gardens and other ornamental plantings that function in the boundary-establishing and home-making process more typically associated with women.

While the introduction of non-native plants has had sometimes severe negative consequences, with the escape of plants from cultivation to become troublesome invasive species, the consequences I wish to consider here are not so much immediately ecological as they are what we might call eco-psychological. That is, they influence the way we imagine ourselve to inhabit our places.

As scholars have noted, the planting of flower gardens was an almost exclusively female activity:

Annette Kolodny notes that “. . . the letters and diaries composed by . . . women during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries strongly support the speculation that the gardens to which women personally attended were crucial in helping them to domesticate the strangeness of America.” (37)

Discussing Eliza Lucas Pinckney, who settled in S. Carolina, Kolodny writes that

like so many other immigrant women, [Pinckney] brought with her to S. Carolina seeds and cuttings from the landscapes she had known earlier (in this case, in England and the West Indies). To make a home of the place, both needed to be implanted on the alien soil. Physically and imaginatively, in short, the pioneer women of America carried their roots with them. (53)

Kolodny also cites Caroline Kirkland: who notes that cultivated women arriving in Michigan may now find the place less wild and strange and more comfortably homey because women such as herself have planted

Narrow beds round the house” which “are bright with Balsams and Sweet Williams, Four o-clocks, Poppies and Marigolds’ (New Home, 248). By the end of her first three years there, the plantings have become even more ambitious: ‘a few apple-trees are set out; sweet briars grace the door yard, and lilacs and currant-bushes’ (New Home 248), (147).

As Kolodny notes, “Kirkland emphasizes . . . that the garden is achieved ‘all by female effort–at least I have never yet happened to see it otherwise where these improvements have been made at all’” (248).

As the Australian Jill Ker Conway describes in her memoir of growing up on an Outback station in the western division of New South Wales, The Road from Coorain, the planting of flowers was something that women often made enormous effort to accomplish, and its succesful accomplishment was seen as the epitome of the arrival of settler colonial civilization. As her parents settled into their remote and arid homestead, she writes,

It was extremely hard to grow anything when the only water to be had was bailed out of the bathtub after the children were bathed in the evening. There was water deep underground, but it was costly to bore down to it, and the first investment had to be made in good water for sheep and cattle. So there was no garden, no fresh fruit or vegetables, and no way to mitigate the red baked soil, the flatness and the loneliness.” (24)

There is in the scholarship on this phenomenon a tendency to see the women who cultivated these gardens as engaging in an innocent endeavor. Kolodny, for example, discusses how many pioneer women cultivated the “innocent . . . amusement’ of a garden’s narrow space.” (7) And in her book Writing the Pioneer Woman, Janet Floyd discusses the Canadian settler Catherine Parr Traill, about whom she writes: “The cultivation of flowers had a particular resonance, expressing a gentle and wholly unproblematic form of land control.” Curiously, Floyd seems to unwittingly undermine this claim to unproblematic innocence by then pointing out that “Gardening and colonization made an especially apt and resonant–and self-justificatory–comparison for the colonizer: tending the garden expressed the continual effort in keeping ‘nature’ at bay and also suggested attractive, blameless aspects of the task of ‘civilizing’ the colony” (132). I remain puzzled how an action that resonates with colonization can be seen as “blameless,” or why one would feel compelled to insist on it, but such has been the tendency in scholarship on this topic.

I would now like to show how these various strands are made manifest in the work of two settler colonial women authors, Australia’s aptly named Myrtle Rose White (1888-1961) and Nebraska’s Bess Streeter Aldrich (1881-1954).

Myrtle Rose White, published 2 memoirs recounting her own time as a pioneer mother in the arid regions of South Australia and northwestern New South Wales.

White’s husband was hired by the famous patoralist, Sydney Kidman, to manage several sheep and cattle properties.

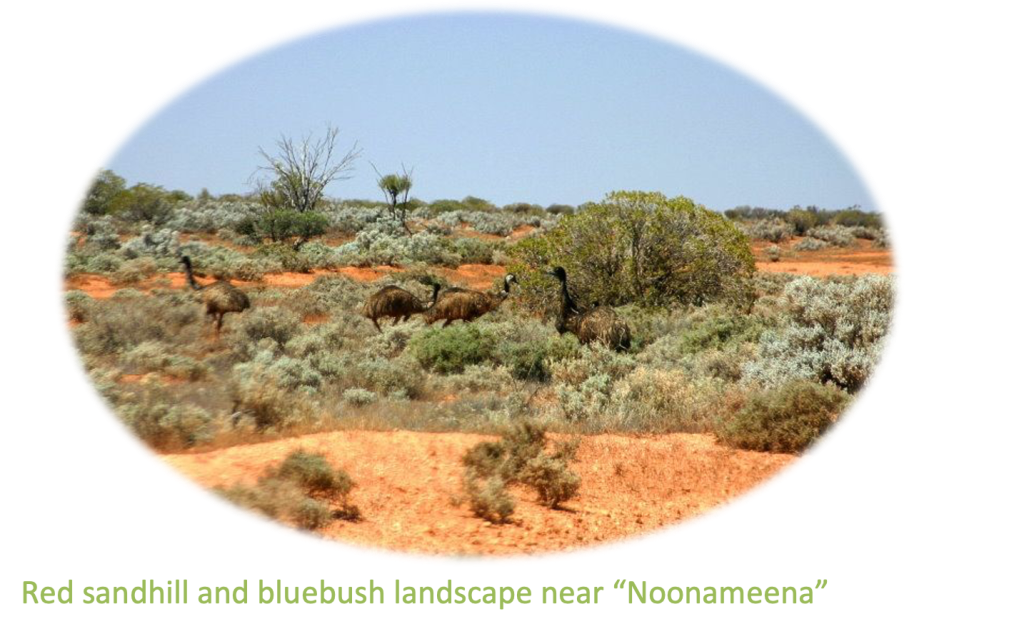

The first was Lake Elder Station (which White renames “Noonameena”), in a very arid sandhill country in South Australia. Here, her husband managed a sheep station. In 1932 White published an account of her time at Lake Elder titled No Roads Go By.

The first year at Noonameena saw us with great plans for beautifying the place. A vegetable plot was fenced in with fine-mesh netting, neat garden beds were turned over, manured, and planted with seed. Two large lawns were laid out and sown with couch grass; roses were hopefully imported from the District City. . . . Purple bougainvilleas, mauve wisteria, a beautiful creeper with white waxy bells, and scented yellow jasmine were planted over trellises. . . Tamarisks that were a dream of frail feathery foliage and plumey pink flowers were put in, with cedars that were to scent the world with their tiny mauve stars, and rattle their polished brown berries like castanets in the wind; and there were grape-vines and citrus-trees, with melons of all varieties. . . . Ah, yes! We all worked and worked, expecting in due course to see the desert blossom like the rose. (White 1949; 65-66)

Alas, it was not to be. All of these plantings withered and died within the year, signifying a failed effort at control. And for all of her evident love of plants, White never did come to appreciate the native flora of the arid landscape on its own terms. Indeed White increasingly grew to despise the country, primarily for its perverse failure to yield to her efforts at transformation.

After seven years, White’s husband was transferred to a different, less arid station, in northwestern New South Wales. She describes this experience in a memoir titled Beyond the Western Rivers, published in 1955.

The book opens with:

“We were seven long years in the open country [as described in No Roads Go By] when our reprieve came.” (1) The reprieve, of course, was transfer to a less arid location. Upon arriving at the new station, she remarks:

“‘Trees!’ I said softly, with satisfaction, my eyes on the dark uneven line against the pale lemon lingering in the sky. I thought of the lone cedar left behind in the sandhills, the only tree near the homestead, and knew this was going to be much better. I loved trees and after years of bare red sandhills I felt that the rest of my life would be too short for me to get my fill of them. To me, green was the most glorious colour on earth.” (20)

This last comment should remind us of Wallace Stegner’s observation that if we are to learn to live in the American West we are going to need to learn to “get over the color green.”

Later, White happily describes her new homestead:

A sturdy earthen bank kept the billabong waters at bay and formed the front fence of the garden. Bush gum-trees marched along the bank, making a delightful break.

The garden or gardens were the quaintest of all features. Little fences and hedges ran in all directions, cutting up two or three acres into sections. Crazy trellises were broken-backed under vines and creepers. Rose-bushes that had grown into trees popped up in unexpected places. A scarlet hibiscus clung to the edge of a lawn. A summer-house with a lean to it like the tower of Pisa tried to come up for breathing space from a smother of purple-red / bougainvillaea. There were the red, pink, and white rosettes of oleanders, the yellow flare of tecoma, shiny leaves of wandering Jew, glistening ice plant, pink climbing geraniums, and a bed of violets. (31)

And, breathlessly, she continues:

” loved the garden, and when I could I stole a minute or two to wander among the green and growing things there. As I have already said, to me trees are the most beautiful of God’s creations, and after the lean years in the red sandhills so many of them were a never-ending source of joy. (31)

Over the years she adds to this garden, and finds great fulfillment:

My roses were a picture to gladden tired eyes. I hung over them entranced and then gathered a huge armful to take the rounds for all and sundry to admire. What matter if floors were half swept, beds half made and many other duties neglected? The garden was a wondrous place on such a morning. Paul’s Scarlet Climber, and deep-red Hadley, covered the entrance porch to the Big House with a piled mass of fragrance. The Golden Emblem climber, with each of its exquisite, elongated buds flushed with carmine, had already yielded seventy-five blooms in the last week or two. The wistaria had never been so lovely as this year. The jacaranda, breaking into a glorious mauve mist, promised to be a serious rival in a day or two. The varnished gold of eschscholtzias and the flaming yellows of every variety of marigold had been making a brave show, and when blue and purple larkspurs were flowering with them their beauty exalted souls of the heaviest clay. . . .

. . . This garden, with many other fragrant corners was truly enough to entice any housewife to turn her back on such mundane things as beds and floors.”

And yet, although the climate of her new home was less arid, it was still fickle and not to be trusted, as she continues:

But, alas, that was in the morning! By nightfall, after hours of the worst dust-storm in many years—though each year has its nerve-shatterers—I looked on a blackened, blasted garden and felt the futility of it all.”(172-3)

In her dissertation “A Not So Innocent Vision,” a study of White and 2 other Australian women settlers, Janette Hancock argues that White’s “planting of rose gardens, fruit trees and lawns reflected the fantasies of a white woman attempting to transform an alien space into a known cultural geography on one level while legitimising the appropriation of Aboriginal land on another . . . ” (359)

And Hancock astutely refers to this planting process as an “Anglicised rite of habitation” (359). White, she continues, is a good example of how

Women could affix their own cultural symbols of ownership on the land . . . and participate in a national story of beautification and development whilst disguising notions of colonial destruction” (360). White’s gardens, she claims, were “aimed at transforming what she saw as the endless, timeless landscape into something that indicated a pioneer’s imprint on the land . . . . The flowers, vegetable plots and lawn were intended to make the unfamiliar, familiar, by stabilising her sometimes foreboding and unpredictable surroundings”(363).

As Bess Streeter Aldrich shows, things were not so different way off in the distant land of Nebraska.

Aldrich’s best known novel A Lantern in Her Hand, published in 1928, is a classic expression of settler colonial ideology. It’s continuing influence can be noted by its choice as the One-book-one-Nebraska selection for 2009. The novel is a fictionalized version of the life of Aldrich’s mother in the character of Abbie Deal. It’s setting is Elmwood, NE, referred to in the novel as Cedartown.

The novel’s Introduction sets up contrast that will pervade the narrative, when Aldrich notes that “Cedartown sits beside a great highway which was once a buffalo trail” (1), and a bit later, “The paved streets of Cedartown lie primly parallel over the obliterated tracks of the buffalo. The substantial buildings of Cedartown stand smartly over the dead ashes of Indian campfires” (1). As we will be reminded many times in novel, the unruly buffalo trail and the Indian campfires, markers of primitive wildness, have been appropriately replaced by an ordered, clean, domesticated civilization most symbolically represented by the flower garden.

When Abbie’s family moves from Iowa to Nebraska the narrative describes the landscape from a wagon in a passage reminiscent of Jim Burden’s observations in My Antonia :

The journey over western Iowa had been one endless lurching through acres of dry grass and sunflowers, thickets of sumac, wild plum and Indian currant. And now [having crossed the Missouri] save for the little clump of natural growth near the wagons, there was still not a tree in sight, not a shrub nor a bush, a human being nor any living thing,–nothing but the coarse prairie grass. (57)

Variations of the phrase “nothing but prairie” recur often in the book: “There was nothing to be seen in any direction but the prairie grass and the few native trees which traced the vagrant wanderings of Stove Creek” (63). As in Cather’s book, prairie grass and native trees are the equivalent of “nothing.”

Similar to Myrtle Rose White, Aldrich regularly contrasts the Nebraska prairie to a more desirable and well-treed landscape. While crossing the grassland of Nebraska, Abbie falls asleep in the wagon and she dreams of “the honey-locusts and the maples,” “the black walnut grove back of his [Grandpa’s] house and the hazel-nut thickets around the schoolhouse.” In this dream she “walked in the cool of the maples and oaks in the Big Woods, picked anemones and creamy white Mayflowers.” However she is awakened by a creaking of the wagon and realizes, sadly, where she was, “the sun shone hot on the flat prairie.” Swaying to the ups and downs of the wagon, “An intense nausea seized her, –the mal de meer of the prairie schooner passenger lurching over the hot, dry, inland sea.” (59). Whether the nausea is entirely a form of motion sickness, however, or a response to the Nebraska prairie, is a bit ambiguous.

In spring, Abbie’s husband plows the land for their first crop.

It’ll be a pull, Abbie-girl, but some day you’ll see I was right. The furrows will go everywhere up and down these rolling hills. Bigger plows than mine will roll them back. There’ll maybe be a town here,” he pointed to the limitless horizon, “and a village there. Omaha will be a big center. The little capital village of Lincoln will grow. . . (69)

This first plowing might be considered another rite of settler colonial possession, as the ever-so intrusive narrator makes clear, speaking from the 1920s:

Prophetic words! A town lies here and a village there. Huge tractors turn a half dozen furrows in one trip across the fields. Omaha and Lincoln are great centers for commercial, industrial and educational interests. Where once the Indian pitched his teepee for a restless day, there are groupings of schools and churches and stores and homes. (69)

After planting local cottonwood trees around the homestead, Abbie imagines fences and a road that will someday arrive,

“And fences. . . Oh, I think, Will, when we get fences, I’ll like it better. It seems so sort of heathenish to come across the country any way. There ought to be nice straight roads everywhere and fences to show where our land begins and ends. And a picket fence around the house yard . . . a nice fence painted white . . . with red hollyhocks and blue larkspur along by it, against the white pickets.” (72)

Never one to let a symbol go unexplained, Aldrich then tells us that:

By 1880 the Deal land was all fenced. The fence was a symbol,–man’s challenge to the raw west. Every fence post was a sign post. More plainly than flaunting boards, they said, “We have enclosed a portion of the old prairie. We hold between our wooden bodies the emblem of the progressive pioneer,–barbed wire. We are the dividing line. We keep the wild out and the domesticated within.” The road, too, which followed the old buffalo trail had been surveyed and straightened. Man’s system had improved upon the sinuously winding vagaries of the old buffalo, and the road, although still grass-grown, ran straight west past the house. The development of the road is the evolution of the various stages of civilization. (111)

After one of Abbie’s newborns dies she lies in bed mourning:

She lay there and thought of the knoll and the prairie grass and the low picket fence against which the tumbleweeds piled . . . where the blackbirds wheeled and the sun beat down and the wind blew. She hated the barrenness of it. If she could put him in a shady place it wouldn’t be quite so hard. But to put him in the sun and the coarse grass and wind! She and Sarah would go over and plant some trees some day. (101)

Of course Abbie Deal was not the only Nebraska settler colonial to pine for trees. And the book notes the founding of Arbor Day: “The next spring (1872), the State Board of Agriculture, through a resolution offered by J. Sterling Morton, a Nebraska City man, set aside the tenth of April, as a special day on which the settlers should plant trees. They called it Arbor Day.” (78) Abbie is naturally delighted.

Within the context I am developing here, it should be clear that Arbor Day is a classic example of settler colonial ideology at work, the elimination of one biome and its replacement by another, and was indeed picked up within a few years in Australia, where it continues to be celebrated.

Aldrich shows us how Abbie, inspired by Sterling Morton, goes on a frenzy of tree-planting that is crucial to the home-making project:

The cedar trees, which Abbie had set out years before, had not lived through the droughts. So now, they put out a new group, nine on each side of a potential path leading up to the front of the house. Lombardy poplars in a long row were set at right angles to the main road, following the track to the barn which Will’s wagon and worn in the thirteen years. “It’ll make a nice shady land road,” Abbie would plan, “and some day we’ll have the white picket-fence.” Yes, the real home was beginning to shape itself.” (114)

then, the next year:

Abbie had her house-yard fence now, so that the chickens could not molest her flowers. Sea-blue larkspur and blood-red hollyhocks flaunted their colors against the dazzling white of the pickets. Flowers in the yard! No one but a rancher’s wife, who had lived in a soddie and up to whose door had come the pigs and the calves and the chickens, could realize what it meant to have a fenced house-yard with flowers. (116)

Toward the novel’s end, on a trip to Omaha in a motor car, Abbie “naturalizes” the “progress” she has witnessed:

In the distance the Platte sprawled out lazily in the morning sun, the thick foliage of its tree-borders green against the sky’s summer blue. There were acres of yellow wheat stubble where once the buffalo had wallowed, fields of young corn where once the prairie grass had grown, great comfortable homes and barns where once the soddies had stood. There were orchards and pastures and cattle, and a town nestling under the sheltering shade of huge trees. And soft white languorous clouds slipped into the east. (236)

The settler colonial transformations Aldrich is celebrating, the replacement of prairie grass with wheat, of buffalo with corn, are framed by references to the Platte and to the langorous clouds, as though they were as natural, and inevitable, as the flow of water and the movement of clouds.

In his book Grassland: The History, Biology, Politics, and Promise of the American Prairie, Richard Manning discusses this sort of transformation of prairie flora by the settlers. He focuses on the work of Frank Meyer, the US Agricultural Dept. employee who travelled the world, especially central Asia, in search of plants to introduce in the American West, and explains that “. . . much of what lay behind Meyer’s work was the blank slate approach to the American West, that it simply had to be torn down and rebuilt botanically from the roots up” (172-73).

Manning notes that “In a Peking nursery, [Meyer] found Syringa meyeri, which every plains housewife came to know as a lilac bush, the fixture of farmhouses from Texas to Manitoba.”

“One might legitimately ask,” Manning continues, anticipating your possible objections, “how there is harm in all of this, something as simple and basic as a farmwife planting lilacs round her doorstep? In some cases,” he avers, “there probably is none, other than continuing our European worship of trees.” However, he concludes in a provocative phrase I have echoed in this paper’s title,

Those lilacs disconnect one’s yard from the prairie that is around and so disconnect our lives from reckoning with the real wonders of the grassland (173).

Surely, I would assert, disconnecting one imaginatively from ones place in the world, and fostering an alienation from the larger ecology of ones home bioregion, is not such an innocent activity for, among other things, it exemplifies and encourages unsustainable cultural practices and the continuing degradation of the larger natural ecology. The literal lilac by the door did not cause the dust bowl, did not drive the bison to near extinction, is not now causing a crisis in pollinator ecology, but the ideology and imaginary it represented and reinforced certainly did.

What Manning hints at, and what I am emphasizing, is our need, if we are to become prairie dwellers, to cultivate not settler, not frontier, not pioneer, not Nebraska or Kansas imaginations, but prairie imaginations. The lilac by the door, however sweetly it smells, can not help us do that.

Let me quickly conclude with an alternative, native plant gardening. And I’ll give a plug for a former student’s book, Ben Vogt’s A New Garden Ethic. Which passionately argues for the use of native plants as an alternative, one might say a decolonial, form of gardening, one that connects us to, rather than alienating us from, our place in the world.